Rob Bremner - Documentary Photographer

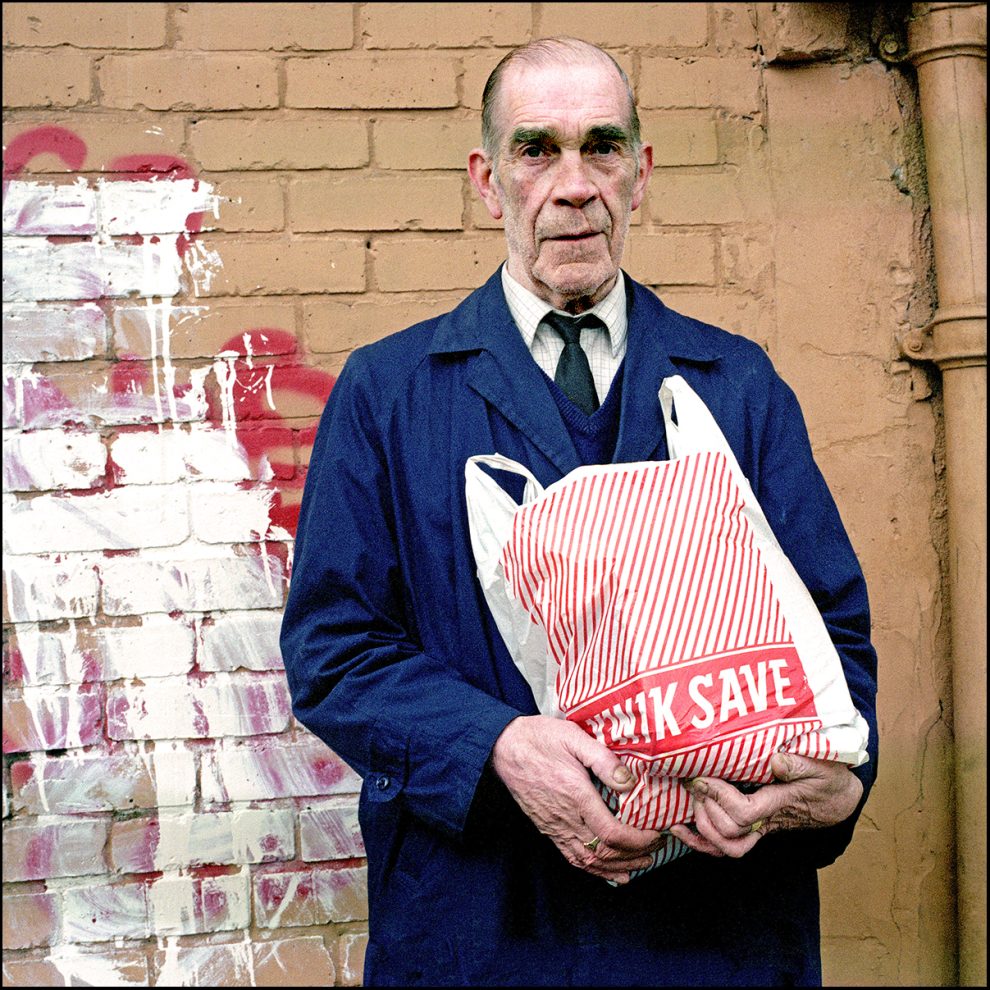

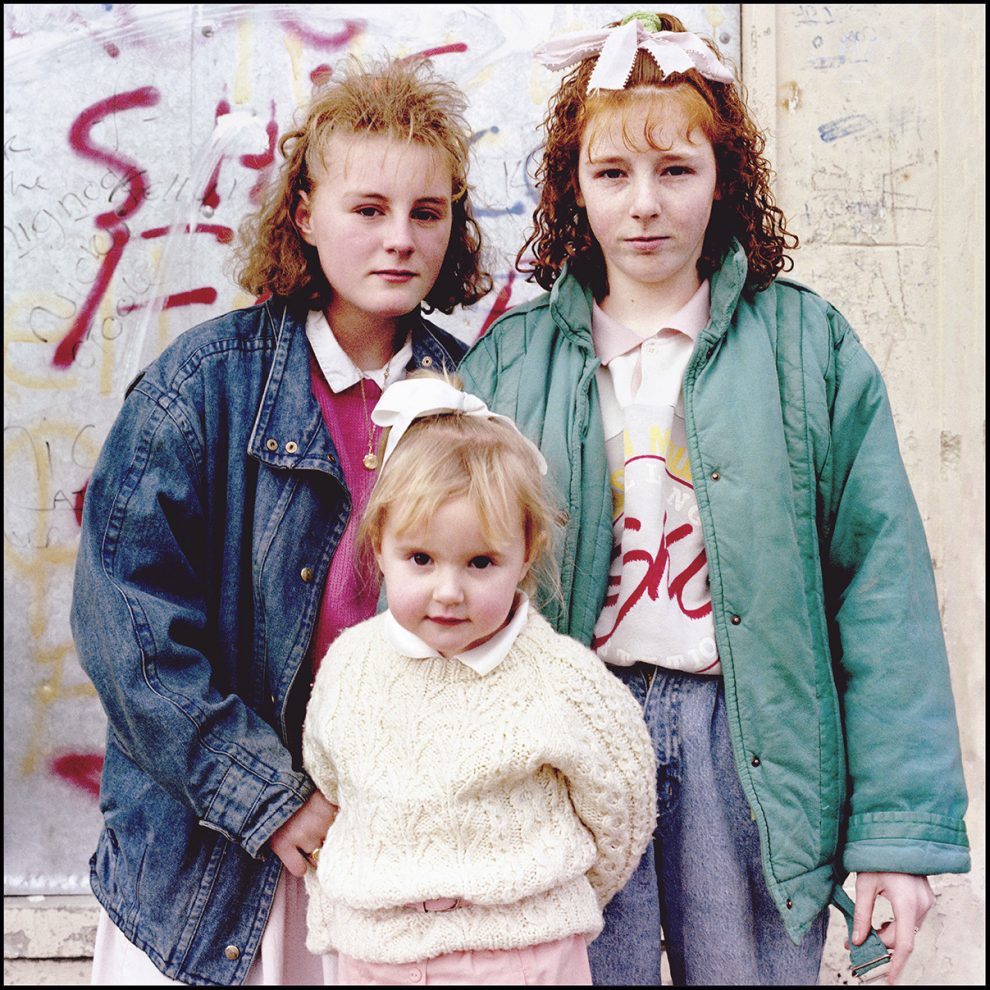

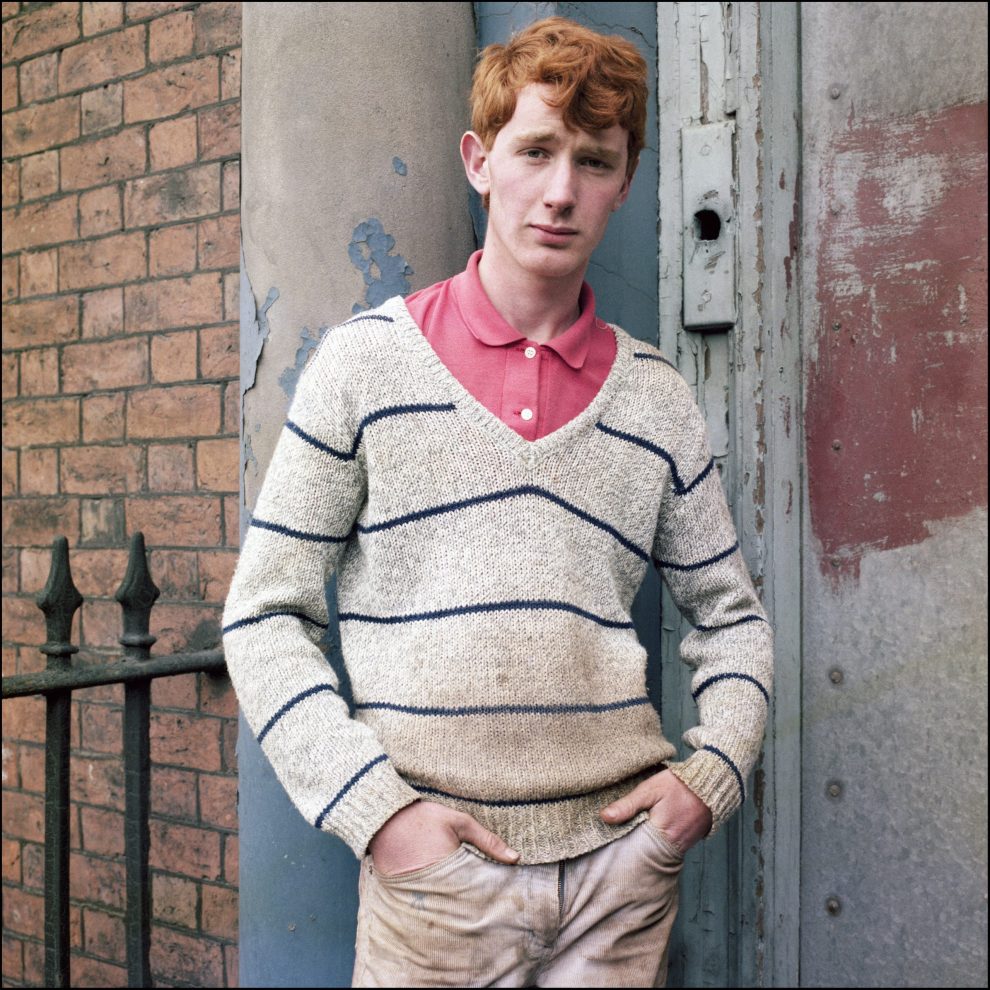

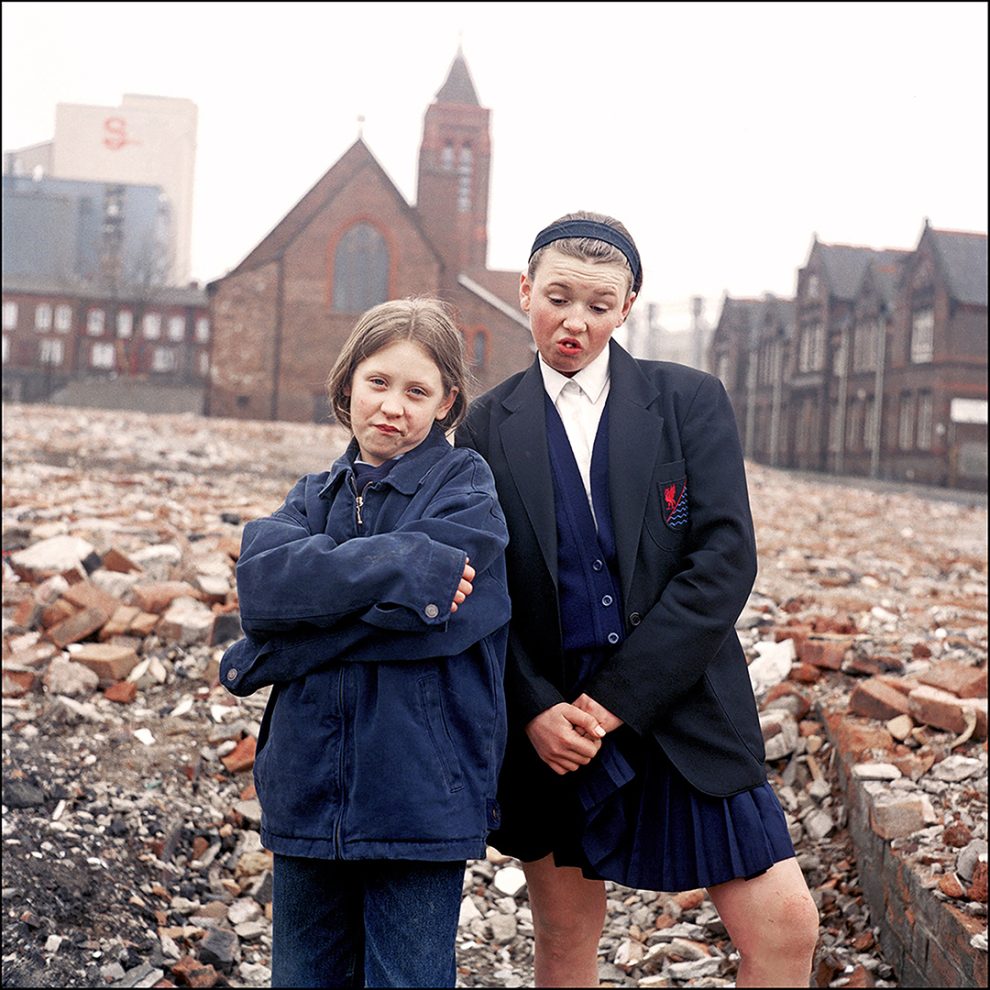

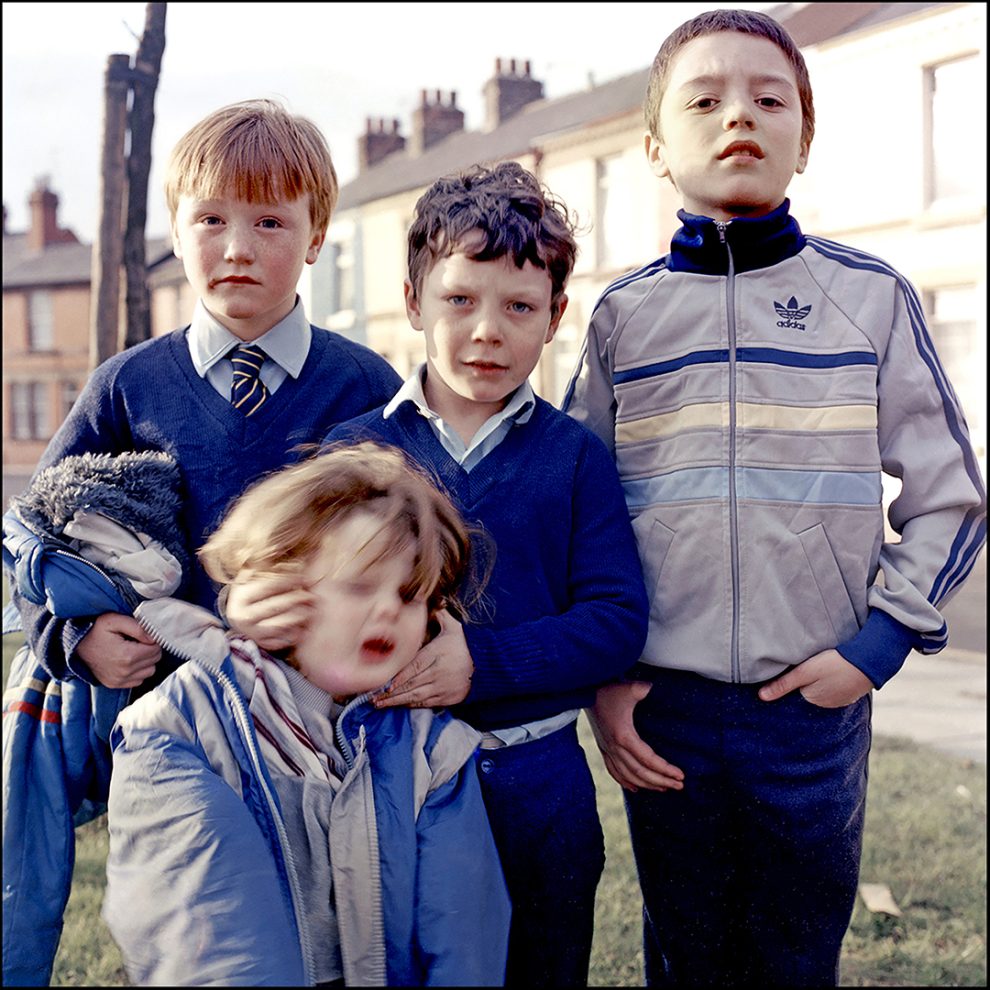

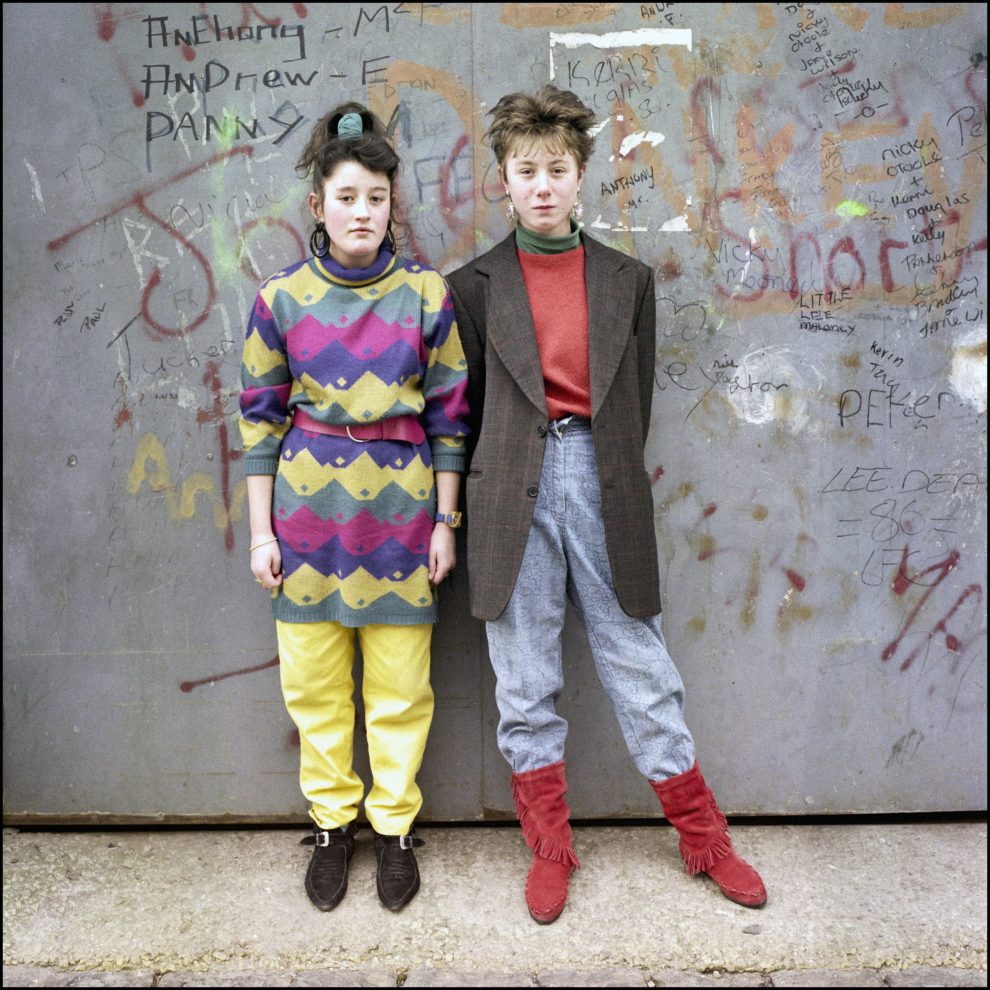

Rob Bremner is a Scottish photographer known for his striking images of Liverpool’s Everton and Vauxhall neighbourhoods in the 1980s. These areas were considered among the most deprived in Britain at the time, but Bremner saw beauty and humanity in the people who lived there. He spent years capturing their stories on film, inspired in part by his mentor and friend, the renowned street photographer Tom Wood.

Born and raised in Wick, a small fishing town in the north of Scotland, Bremner moved to Merseyside in 1983 to study at Wallasey School of Art. It was there that he met Wood and crossed paths with another influential photographer, Martin Parr, who was working on a series of images about New Brighton.

Despite a brief stint at Newport College of Art in Wales, Bremner found himself drawn back to Liverpool, where he immersed himself in the local culture and helped Wood in his darkroom. The city was facing serious challenges at the time, including high unemployment, drug use, and organized crime. But Bremner saw hope and resilience in the people he met, and his photographs offer a unique window into this turbulent era of British history.

As a follower of Rob’s Instagram and his photography, I managed to ask him some questions recently.

Q: Rob, how are you doing – what are you doing Photography project-wise right now?

Well, you know, one of the reasons I’m living up here in Scotland is because it’s so cheap compared to Liverpool, or anywhere else. I don’t take photographs up here. I was caring for my mom and dad before they both passed. I want to get back down to Liverpool and take some more photographs. But I’m really hesitant to be doing that. Because a lot of my clients, you know – Times Education Supplements and all of these people that I used to work for – are no longer around. And it’s a case of, do you really want to wind up doing public relations work and stuff like that? You know, it’s all very well going out and taking and taking photographs yourself. But it’s very difficult to make a living doing that.

There are so many photographers leaving college – now, even back in the 90s. I was doing Times Ed and I remember speaking to the guy that worked for them, and he said, ‘Well, there’s more people in college than there are professional photographers in the entire country’. So, it does start to become competitive, I’m sure. I can do family portraits and stuff like that. And I don’t even mind doing the odd wedding, you know, just do it in the documentary style. So yes, I’d like to go down to Liverpool for three months, to see how it pans out.

Q: How did you get into photography and has it always been a profession for you more than a hobby?

It’s a bit of both – I’m not actually shooting anything at the moment, but that’s because of my parents being dead.

I was going to do a thing on my family. My Dad had nine brothers and three sisters, and half the town was related to me, and all they do is gossip and talk, go up and talk about each other behind their backs, as any small town does. So that’s what I was originally going to do whilst I was here, you know, because I had a few good ones that I’d shot that year and stuff like that, but then I just abandoned the idea.

You know, too much on my plate with Dad being with me 24 hours a day anyway. But I’ll get back you know, it’s not something that you forget to do you know, you get your background right. I’m not going to have much problem getting back into doing my own stuff. And then I’m going to try and see if I can raise money from housing associations. Because I wouldn’t mind photographing everyone in Liverpool, 250,000 people, six years, 200 people a day, five days a week with two days off in two weeks holiday – I’ve worked it out. I can’t photograph everyone, but I can ask everyone.

Q: Wow that sounds like an amazing, but huge project?

It’s just a way of doing it. But it’s a way that if you can raise the money for it, then it’s ongoing. It will give you finance for six years to complete it. By then I’ll be 59. Now I’ll be reaching retirement. So, you know, I can go out every day, I don’t mind going out every day and just taking photographs, particularly if there was no client, in the sense that you have to get less right, because it has to fit into this newspaper or magazine. You know, a lot of the people I work for, you’d be using flash guns and all sorts of things that I wouldn’t use for myself.

So about how I started photography. I’m waffling on…

Q: That’s okay. It’s good to get the context. If we could go into a little bit about how you started – because you captured the 80s and 90s perfectly.

All of that work and everything was done, mainly in a four-week period when I was shattered, and the last year at Newport, in 1987, it was just a case of me asking everyone, ‘excuse me, can I take your photograph?’, type of thing.

Q: And that approach worked well for you?

I still use that, you know. I was doing a job last year was for a company in Liverpool and I went around Everton, and it didn’t seem that much different. I think a few people, couple of school children, looked a little bit dodgy at me, but apart from that all you do is ask. I don’t mind people saying no, I’m always polite anyway. They’re normally polite back as well. If you don’t ask people, then you wind up with these shots where you’re trying to pretend that you’re not actually taking photographs of the people that you’re photographing. And if you do that, then it’s not really about the people that you’re photographing, because they’re too far in the distance.

I had an advance when I went and worked with Tom Woods. I worked there for a long time, and Martin was photographing New Brighton, as well. So, I could see them simply work and they were positioning themselves. And that was probably quite an advantage.

I’ve got nothing but admiration for Martin Parr. He’s always been so really, really organised in a way that most of us never could be – the amount of discipline, you know, he spent three months just publicising and going around colleges with the ‘New Brighton work’, when he’d finished that. I’ve seen it twice: once when I was in Wallsey, and then again when I was in Newport. He was doing the rounds, speaking to people and publicising himself, and that takes a lot of time and effort.

Q.In your photography – it looks like you have a great connection with your participants?

My view of it is that I was a student and they were helping me, you know, it’s a kind of collaboration. And all I’m really doing is saying: ‘stand there, look into the camera.’ And moving them slightly, if one head is in the way of another. I’m not asking them to do anything that’s not natural. You know, when you look at a fashion photograph or something like that, it just looked a bit ludicrous, with the silly poses and everything. I was never gone for that. I was always just trying to get people as naturally as possible. Hopefully, not smiling. Yeah, I just ask them not to smile. If they smile, it turns the image into a snapshot.

It just doesn’t work – that looks like something else. There are 1000s of photographs you see on Facebook of snapshots of people posing for a camera. There was no point in doing that because they could do the selfie themselves. And there’s so many selfies out there now, they’re never going to be quite deep. Really, they’re not a document of anything, they’re just how people would like to see themselves, rather than any kind of reality, but for documentary photography, you want people to be looking at it in 50, or 100 years’ time. As moments, when we’re all gone, you know, evidence that we existed really.

Q. Is your style your own or were you influenced?

Everything from Eugène Atget to Paul Strand, I had all the books as a co-worker with Tom for a long time, and Martin had really big libraries of photography books.

Back in the 80s, when I was in college, it was monographs, a lot of them, and they cost like 100 pounds or a couple of 100 pounds, because they were really finely printed. And I used to edit for Tom as well. We’d go to the pub every Friday, Saturday night, type of thing, and he would take down the box of photographs and go over them.

So I was kind of trained to do that. So when I was looking at those books, I was also ‘editing’ them, if you see what I mean. Like, you would pick out the good photographs in a book – not just because it’s by Lee Friedlander or a Gary Winogrand but because were they good photographs. I would argue that there’s about four or five good photographs in the Martin Parr book ‘New Brighton’ out of the forty – the rest are OK, but there’s four or five outstanding photographs. And Tom would edit as well. So, you know, there’s a large process of editing, but I’ve got all the images of the history of photography in my brain and how photographs work. You know: why something balances, if you have a post going up in your photographs, you know, you never have the post centre? I got that from that Lee Friedlander’s photographs.

It’s just ideas about how you compose and how photographs work. You know, I have a few, I think I’ve got about 200, that I think work and all the rest are pretty crap. Which is fine, because I’ve not, you know, got the amount of time that Tom has and stuff like that. So yeah, it was the same way with Martin, and I expect them to have more photographs than me because like, they’ve been going out all day, all the time. And when I was worried again, that I couldn’t afford that film and colour and process and, and stuff like that… So, you know that if you’ve looked at the cost of the ‘New Brighton’ work, that probably ran to £1000s. And Tom’s bus book, ‘All Zones Off Peak’, (1988) was something like 20 or 30,000 roles of film. So, you can imagine when you’re gonna shoot 10 rolls of film and paying to get that processed, then prints back, then press, and then finished handmade prints. You know, you’re never going to see your money back. The same way with Chris Killip – I think he spent about £20,000 getting his negatives retouched for that ‘Another Country’ exhibition.

The problem with British documentary photography is that we don’t have very many people that manage to sustain it for their entire lives. They leave college to do a few years, realise that you can’t make any money doing exhibitions and they have one or two – they may be successful, even for a couple of years. But soon as the arts money runs out, there’s not a lot of places for them to go.

Q: To the cost of photography – I know you started off on film; have you move to digital cameras?

Yes, and I need to buy a GFX Fujifilm camera. It’s the only one that will do, none of the rest, because I’m doing portraits. And I’ll be doing landscapes and I’ll be doing candid work. And it’s about the only camera on the market. I want to earn my living as a photographer, as an artist, yes, yes.

Because I know that there’s no market in art. I never really went to school, I got excluded quite early on in my schooling career, I never went, basically. When I left school, I got a job as a garage, which I absolutely hated. Six in the morning I was supposed to be an apprentice mechanic, but I just hated working there. And when I left that, I went to the local photographer’s shop – this was a YTS (Youth Training Scheme) in Inverness, with a press photographer, you know, 23 pounds a week, or whatever it was back then. I’d gone and asked the local wedding photographer who got me that job. I’d been starting work at 7 in the morning and he didn’t start until 10 and that was the reason I wanted to be a photographer.

That was a six-month course. You know, it was designed because I left school in 1980 and youth employment was really skyrocketing. So when I did that, I really enjoyed it. I went back to college then and did a few ‘O’ levels and ended up in Central Park when Tom Woods had just started teaching. But basically, I just did a YTS, and then it was Central Park and Tom.

Q: your captures of the 80s and 90s have a unique look because the country was going through some turmoil at the time.

But the same thing will happen to your photographs now, in 20, or 30 years’ time.

They improve, documentary photography improves with age, because everything changes. In 20 years’ time, there probably won’t be so many cars on the road, we’ll probably be a little bit broker as a country as well, with the way things are going, but it’ll change continually, the technology, everything, fashion – and that’s why photographs and what was everyday in the 70s the 60s and the 80’s, is to me, like that old woman, sort of walking around with a headscarf. So, they used to look like proper grannies and not, well, you know, the blonde hair and the fake boobs that grannies have now, which will probably look a bit weird in 20 years’ time.

Q. what is it about the new Fuji Medium format cameras that you like?

Well, as a pro, I’m probably going to buy a 45 millimetre lens so I can use that.

If you’re doing architecture, urban landscape, you want your lines straight in the background, the distortion, you know, doesn’t work. Distortion alone, works if you’re doing candid stuff; it doesn’t work with a formal portrait.

Or an urban landscape. If you look at anybody’s sets, anything good, from Walker Evans to Eugène Atget or anyone, the lines are always straight. So that’s my problem just now: it’s trying to figure out whether a 63mm is just a bit too long for doing street portraits. Because I did a thing for Elle magazine, just a fashion shoot, a couple of years ago and when I put it on to 63mm, I was standing in the middle of the bloody street as the traffic was coming. And that’s okay in a job, because you can just ignore the traffic; it’s only taken a few minutes and you can’t be doing that if you walk them down Scotty Road, because they will run you down.

Q. You’ve mentioned in discussion quite a few past magazine projects and papers – can you tell me more?

Oh yeah, I’ve worked for The Times, Nursing Times, The Guardian, Nautilus Telegraph, Inside Housing and Liverpool Housing Trust, Construction News – just about everybody, every trade union; trade unions were the backbone of what I did.

We did make a reasonable amount of money doing that, because if I did a strike, I’d be the only photographer there, apart from one other. And he would only get paid 15 pounds. But, I would actually phone up all the trade unions and I would get a half-day, a week. I would end up with, like 1000 pounds, and then I would put them on to ‘Inside housing’, if it involved several servants, or anything like that, teachers.

I would spend a year traveling in India taking photographs because I phoned up every trade magazine and got a half-day off them, and stuff like that. So you get 20 half-days, you know, that’s two and a half grand. It’s not enough, but it’s enough to pay for your trip. And I did the same thing with orphanages in Romania. I think I spent a month photographing six, or seven of them.

Those were things that you did then and all of the magazines have kind of gone now. You know, that’s been my reluctance for moving back. And that’s why I want to do three months, I want to make damn sure that I’m making a living, because being poor in Liverpool is not good in any setting. That is not somewhere that you want to be.

Links:

https://www.robbremnerphotography.com/

https://www.instagram.com/robbremner_photographer/

https://britishculturearchive.co.uk/product-category/rob-bremner-prints/

Others:

https://tomwoodarchive.com/