Stories from the Ukrainian front

The Russian war in the Ukraine is being brought daily to us through television, radio and press reportage, and a key dimension of that conflict has been the unfolding plight of millions of displaced refugees.

The war has served to yet again remind us of the power of the visual image to act as witness to the pain and death, disruption and displacement it has wrought on the country’s citizenry – and, of course, it has brought to the fore the vital role played by photojournalists covering the conflict.

PhotoBath is privileged to host the work of two associates who have been documenting the moving stories of the consequences of the war from both sides of the Polish/Ukrainian border – documentary photographer, Chris Roche, from within Ukraine, and photojournalist, Chris Niedenthal, from the arrival point for many fleeing the country, Warsaw.”

For Chris Roche, his black-and-white images feed into his evolving work into borderlands, while Chris Niedenthal’s images are set in his long-term chronicling of the post-Soviet era in Eastern Europe.

Christopher Roche

Having completed my five-year photographic project ‘Devotion’, I was reflecting on what new theme might spark my imagination. One of several ideas I had was ‘Borders’, particularly the borders of Europe. An exodus of refugees fleeing Syria and sub-Saharan Africa had made Europe’s borders contentious once again, as had the sabre rattling from Putin. My plan was to visit the refugee camps on the islands of Lesbos and Lampedusa as well as the Donbas region of Eastern Ukraine. I had directed many TV commercials in both Ukraine and Russia, flown between Kiev and Moscow several times and was curious to see how those on the borderlands lived. Well, Putin’s plans usurped mine so early April I headed to the border between Ukraine and Poland instead. This is a border that has shifted many times over the last century or so, with the now Ukrainian city of Lviv being part of Poland for hundreds of years.

I made my way to Przemsl – a town on the Polish side of the border which was invaded by both the Nazis and the Soviets during the second world war. Over the last few months as many as 500,000 Ukrainian refugees have passed through the town looking for safety in the west. By the time I arrived I found more volunteers with stockpiles of blankets and food than refugees – who had already been moved on to Warsaw and beyond. I decided to head on into Ukraine and was lucky enough to find a spare seat in a van that was delivering specialised cardiac equipment to a hospital in Lviv. Over the next few days, I visited the refugee camps along the Ukrainian side of the border. There are estimated to be around 7 million internally displaced Ukrainians who are either unable or unwilling to leave the country. I met one mother who didn’t want to leave her 18-year-old son who had just been conscripted (all healthy men aged 18-60 cannot leave the country but must stay and fight). Another mother lost her baby’s papers in the original rush to the border and is not allowed to leave without them. Another family lost all their documents in the rubble of their home in Mariupol. A further woman had mental health issues and wasn’t psychologically equipped to cross the border unaccompanied to an unknown future. There were endless examples of such cases.

The railway station of Lviv had become one of the main hubs for the exodus. Daily, thousands of refugees tumbled out of the trains coming from the terror in the east and south. They made their way to the army of volunteers serving up free meals and the voluntary doctors doing their best to serve patients with a host of differing needs. This all happening amidst the Covid pandemic and air raid sirens wailing overhead. The refugees packed themselves onto an endless stream of buses heading west and hopefully to safety. Watching these scenes, reminiscent of wars from a previous century, and seeing the faces of women, children and the occasional man, consumed by a mixture of fear and relief, I wondered how do they explain what is happening to their children.

Chris Roche’s photographic work can be seen here:

Chris Niedenthal

Where do I begin? Poland is a neighbour of Ukraine, so perhaps that is where I will start.

Neighbours tend to either love each other, or hate each other. And yes, this has historically been the case between Poland and Ukraine. I shan’t go into the details of this sometimes tragic love-hate relationship – except to say that luckily, we are in a love phase right now. Not so much the Polish government, more the people of Poland, the ordinary citizens on the street, so to speak.

I have lived in Poland for coming on 50 years now and, while I cannot say I know everything, I do know a thing or two about Poles. They are open-hearted (OK, they CAN be open-hearted), friendly, interested in others – meaning foreigners – helpful and hospitable, etc. etc. The usual stuff. When Putin invaded Ukraine on February 24th, 2022, and all hell broke loose there, Poland opened its border and over time, let in several million Ukrainian refugees. Apart from the open border, there wasn’t that much in the way of government help: volunteers and non-governmental organisations immediately jumped into action and organized assistance for a hell of a lot of people. Poles and Ukrainians are culturally relatively similar, their languages have similar roots, so the hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian women, young and old, plus thousands of children (men had to stay and fight) came mainly to Poland. Many of them fled further west, but right now perhaps a million have stayed in Poland, finding work, paying taxes.

And that’s the remarkable part of the story: no refugee camps were built – ordinary people invited the Ukrainians to stay in their homes for as long as necessary. My own son, as soon as he saw a woman and her son sleeping in a car with Ukrainian number plates, immediately left them the apartment he was renting and moved in with us for several months. There are thousands of similar stories out there, in Warsaw and other towns and cities.

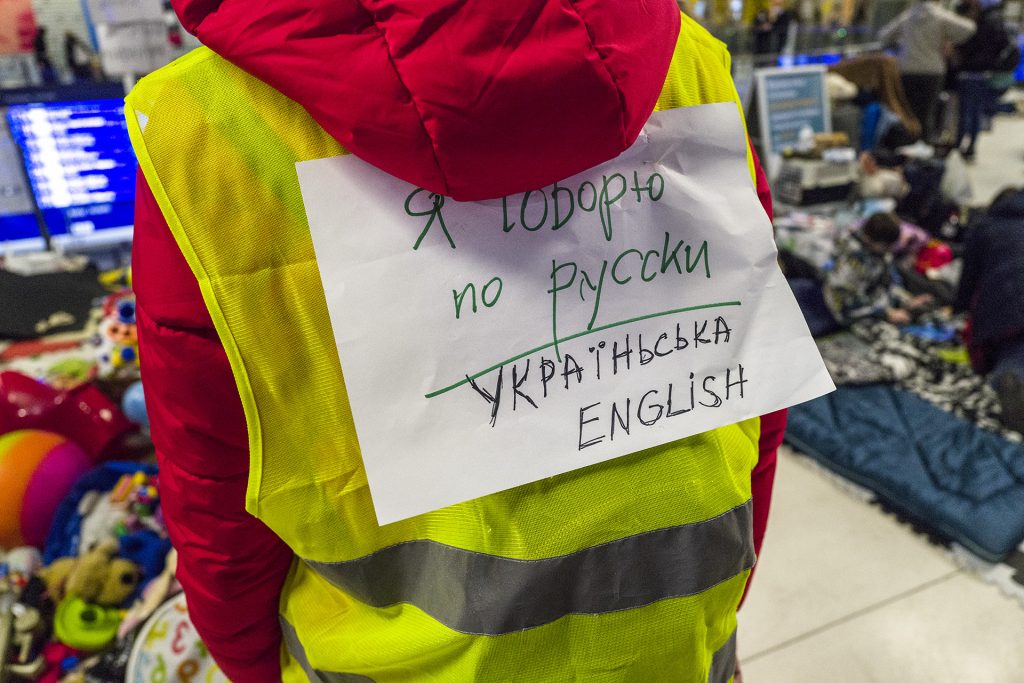

Which brings me to the photographs I shot at two Warsaw train stations (East and Central) in the days following the outbreak of war, when thousands of escaping Ukrainians flooded – quite literally – those stations after crossing the border. The scenes were chaotic. Maybe it was organised chaos – but it was chaos nonetheless. Relief mingled with tears. However, it was a pleasure to see the number of young volunteers helping everyone in need. Food, water, medical assistance was available on the spot. So too was information about the possibilities of accommodation in and around Warsaw. Every so often someone would come up and offer additional places to stay.

Many people came in with bags full of food and toiletries. Even cat and dog food was brought in – to a special corner for canine and feline refugees – and there were many of them. Still, hundreds of people were lying around the station area in sleeping bags, under eiderdowns and blankets, resting and sleeping after their long, exhausting journey from Ukraine. It was an amazing sight to see. All the assistance given and received – even way after midnight – was clearly palpable and made everyone (myself included) feel that when it comes to the crunch, there is a lot of goodwill in the world.

As soon as the war broke out thousands of people came to protest the war outside the Russian Embassy in Warsaw. Ukrainians, Poles, Belarussians alike. Police sealed off the street, and allowed the protest to last as long as it wanted. Later on, after the news of civilians being shot in cold blood by Russian soldiers on the streets of Bucha, a group of young people pulled bags over their heads, tied their hands behind their backs and lay down on the pavement outside the embassy, pretending to having been shot.

On another day, when it became clear that Russian troops were stealing whatever they could in the towns they attacked, people piled household junk on the street in front of the embassy. Washing machines, teapots, fridges, toilet seats, stoves, microwaves – all smeared with red paint to imitate the blood spilled in Ukraine. The same too, with ladies’ underwear and other personal items reflecting the amount of raping going on during the Russian attacks.

A photographer can see a lot of nasty things during his working life – but I must admit, I had trouble dealing with everything that I saw in Warsaw during the few months since the brutal war started. And that was just Warsaw. I hate to think about what could be seen in the war zones of Ukraine.

© The images contained in this article reside with the respective photographers – for Any use of these images please contact PhotoBath or the individual photographers:

chrisniedenthal@pro.onet.pl and clbroche@hotmail.com.